We have almost completed our work at the station at 42°N 19°W! It has been a tight schedule, with mapping the area first to make sure that the stage is ready for seafloor gear deployment, followed by ‘the plankton block’ and sediment sampling with the benthic part.

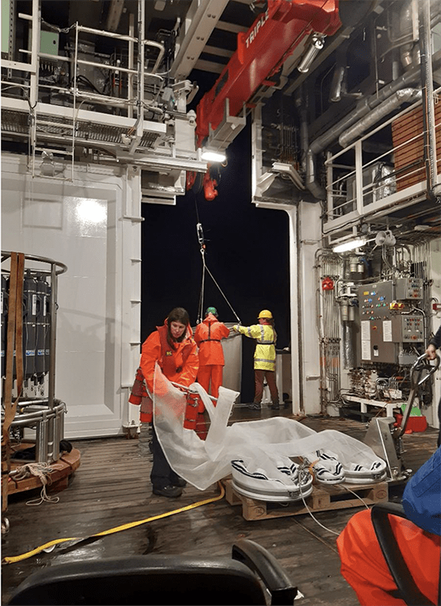

On this trip, the Senckenberg plankton group brought three different nets to sample the water column: A large hose net, an array with multiple nets of differently sized apertures, and the Bongo net. The latter consists of two pairs of nets and, due to its shape, is named after the bongo drums. All of them are dragged or lowered over the side of the ship to collect creatures from the water column, and are rinsed afterwards to fix the samples. Amongst other objectives, the focus of investigation is microplastics in zooplankton stomachs (yes, zooplankton does have a have little stomach!) to estimate how far the synthetic material has entered the food chain already. We also have the Neuston catamaran – an instrument to collect and analyse larger parts of floating plastics.

To discover the seafloor, its composition and inhabitants, we have the OFOS, a towed camera system along with a variety of bottom sampling instruments. Ground truthing along a deep-sea transect is done with the epibenthic sledge (EBS) which sweeps over the floor and collects the uppermost layer of seafloor material. Point location sampling is carried out with a boxcorer and a multicorer.

Usually, at least in the deep sea or abyssal plains, the seafloor composition is clay, silt, and sometimes sand. At those latitudes, the mean sedimentation rate – i.e. the rate at which particles accumulate on the seafloor – is around 2.5cm per hundred years. Hence digging half a metre into the seafloor means looking back twenty centuries!

On a sad note, a young blue shark who got tangled in a long fishing line came up on deck along with the EBS. Longline fishing is a method for targeting meso- and bathypelagic sea inhabitants, and it has a long and controversial history. One line can be up to 62 miles long carrying about 10,000 baited hooks at intervals of several metres. Some techniques demand dragging the line behind a fishing vessel, others drift in the water column until they are retrieved. The non-selective nature of longlining is a major issue as the amount of incidental bycatch of untargeted species such as dolphins, penguins, sea turtles, sharks, or sea birds. In particular it is estimated that per year, more than 300,000 birds drown being hooked on longlines (https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tcam.2013.09.006). Mitigation attempts are made to reduce preventable bycatch involved in industrial open ocean fishing, but such findings are a reminder that consumer education and ethical practices still have a way to go in the modern world.